News

Summers Will Not Finish Semester of Teaching as Harvard Investigates Epstein Ties

News

Harvard College Students Report Favoring Divestment from Israel in HUA Survey

News

‘He Should Resign’: Harvard Undergrads Take Hard Line Against Summers Over Epstein Scandal

News

Harvard To Launch New Investigation Into Epstein’s Ties to Summers, Other University Affiliates

News

Harvard Students To Vote on Divestment From Israel in Inaugural HUA Election Survey

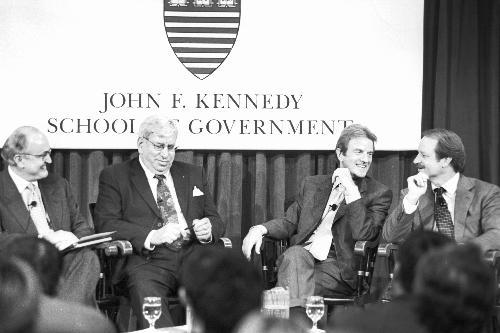

United Nations Officials Discuss ‘The Search for Peace’ at the IOP

Three United Nations officials drew on decades of experience to urge a cautiously optimistic view of U.N.-mediated peace and nation-building at a panel at the Kennedy School of Government’s ARCO Forum last night.

The lively, contentious panel, entitled “The Search for Peace,” brought together three men who have held or currently hold the position of Special Representative to the Secretary-General (SRSG) of the U.N.

Kirkpatrick Professor of International Affairs John Ruggie, who moderated the event, described the SRSG position as possibly “the most difficult job in the entire world.”

According to James G. LeMoyne ’74-’75, who is currently an SRSG overseeing the U.N. presence in Colombia, the job entails peace-keeping and nation-building efforts.

But he said “the U.N. has no clear mandate for peace-building.”

“I can promise you,” he said to audience members interested in pursuing his line of work, “you will never have enough money, never enough time, never enough international support.”

Jacques P. Klein, a current SRSG, said he struggles with determining when it is necessary for the U.N.’s peacekeeping forces to intervene.

At times, he said, member nations have “no national security interest” threatened, but “what’s going on is so egregiously wrong that something must be done.”

The three speakers emphasized the current relevance of these moral quandaries.

Bernard Kouchner, a former SRSG and founder of Médecins Sans Frontières, said that the U.N. must ultimately deal with the threat posed by Saddam Hussein—but the time is not right.

“I don’t understand the timing of Mr. Bush,” he said.

But he said that in some situations preventive measures are necessary, “otherwise it will always be too late.”

When the U.N.’s peacekeeping forces move in, the situation can grow even more complex, Kouchner said. He used as an example the U.N.’s intervention in Kosovo, for which he served as the SRSG.

“In Kosovo we were aware of the victims, [but our] mandate was particularly unclear...We had to set up a state from garbage problems to the constitution,” he said.

LeMoyne was bleaker about the chances of lasting success in the U.N.’s nation-building mission.

He said the U.N. has had only two unqualified successes in that category— Germany and Japan after World War II.

“Imagine what would have happened if we had left,” LeMoyne said, comparing the 25-year commitment to those nations to the two or three years he said the U.N. has recently devoted to areas such as Kosovo and Rwanda. Often, he said, the “transition mechanism” that brings order to countries of chaos does not exist.

But the two other panel members objected, calling LeMoyne unnecessarily pessimistic.

Klein cited East Slavonia, for which he served as an SRSG, and his ongoing work in Bosnia-Herzegovina as successes.

Kouchner said the very existence of the U.N. as a force preventing human rights abuses within nations—rather than as one mediating conflict between nations, as originally intended—is itself “a great success.”

LeMoyne acknowledged these successes, but noted that Klein and Kouchner worked in “the Rolls-Royce of U.N. missions—white people are dying in Europe.”

But the panel ended on a hopeful note.

“Every great change in history has been impossible,” LeMoyne said. “All these things are not possible until they happen, until people give a damn.”

Want to keep up with breaking news? Subscribe to our email newsletter.