Separating the Message from the Messengers

Last week I began to realize why so many people hate peaceniks. I was at Suffolk Law School with Jason L. Steorts ’03 for a taping of Laura Ingraham’s conservative radio show. We were slated to appear on the show to give “college students’ perspectives” on why we thought intervention (Steorts) or non-intervention (myself) were the right move in Afghanistan. We were bumped from the show—apparently President Bush’s press-conference and a telephone call from Sen. John Kerry (D-MA) were more important than what a couple of dumb college students had to say.

Unfortunately, not bumped were representatives of a Boston coalition for peace. The man had long black hair, tied back into a pony-tail, and a poorly trimmed moustache. The woman had her head shaved to ear level topped by a shock of short, bleached-blond hair. They looked like the kind of pinko-liberal bogey-men who Salient editors see in their nightmares. They spoke immediately about the United States’ legacy of propping up murderous Middle Eastern dictators and violating human rights around the world. When asked what peaceful alternative to war they would suggest, one offered that America should immediately decrease the cost of AIDS drugs to Africa.

Ingraham and her vociferous crowd eviscerated the two neo-hippies and they left having accomplished little other than too further entrench thousands of Ingraham’s right-wing listeners in their hatred of egg-sucking anti-American liberals. As I lay in bed later that night I had two thoughts: one was that I was grateful to have been bumped by Kerry and Bush, for fear that making an argument for peace after those two would have meant an almost certain stoning during a commercial break. The other was a slow awakening as to why so many people are often resistant to arguments for peace.

My opposition to war made watching the two peacemongers all the more difficult. In their holier-than-thou arguments and shortsighted blaming of the U.S. for the events of Sept. 11, these and many other activists ignore the more logical arguments for peace. Currently, the basic goal of the U.S. should be to prevent any further terrorism and bring the perpetrators of the Sept. 11 attacks to justice with as little loss of life as possible. The question is whether this would be done more effectively through war or alternate means. In terms of preventing further terrorism, a war with Afghanistan does not appear to be particularly effective. While it appears that it took years of planning from a large, well-funded terrorist cell to undertake the Sept. 11 attacks, terrorist acts from members of bin Laden’s network, which is believed to include thousands of members spread throughout dozens of countries, are simply not that difficult to undertake. It is as easy as a well-placed sniper, a car filled with homemade explosives or an envelope of anthrax. Even U.S. Defense Secretary Donald Rumsfeld admits, “You cannot defend at every place, at every time, against every conceivable, imaginable—even unimaginable—terrorist attack.”

When and if the U.S. kills Osama bin Laden, the threat may actually increase if he is glorified as a martyr. As history has shown, most political and religious leaders, whether they be the organizers of the Irish Easter Rebellion, those who died in the Boston Massacre, or even Jesus Christ, proved much more powerful in death than in life.

As President Bush has said, bin Laden is only one man, and the only real way to stop terrorism is to try to round up the terrorists who live throughout the world. To do this, a powerful, international court of law with authority to arrest, extradite and punish offenders must be created. Such a court would require international support from a vast array of countries—the possibility of which decreases with each bomb that is dropped and Afghani civilian who dies. Already the loose alliance of countries “supporting” the U.S. bombing is weakening, and if the war becomes at all protracted then it may dissolve completely. Of course any such court would, on occasion, have to use military force to arrest criminals, and the possibility of deaths would be present. However, these actions would be taken in the form of a legitimate police action against criminals, a far better option than the current war against an entire country.

One need not create elaborate conspiracy theories to claim that the current war is an attack not only against bin laden and the Taliban, but all of Afghanistan, simply look at Bush’s message to Afghanistan: “If you cough [bin Laden] up and his people today, then we’ll reconsider what we are doing to your country.” So, if bin Laden and his henchmen are handed over to the US, Bush will “reconsider” bombing a country which is already on the verge of total collapse because of an extended famine and ceaseless war? The comment “your country” is also an echo of the doctrine of total war, that we are not simply attacking bin Laden or the Taliban or Al Quaeda, but the country as a whole.

Like it or not, bin Laden and the Taliban are in power largely as the result of support of the U.S. during Afghanistan’s war with the Soviet Union (back when their militarism was “freedom fighting” and not its more current and accurate name “terrorism”). The U.S. funded them, built the very camps that bin Laden now uses to train terrorists and supplied them with weapons all in the name of anti-Communism. Now the U.S. is supporting the Northern Alliance, another group of hardened “freedom fighters” known for their corruption, all in the name of anti-terrorism. The mistakes made and deaths caused by the U.S.’s anti-Communist policies of the past are clear. These policies helped bring groups like the Taliban and leaders like Saddam Hussein and Osama bin Laden to power, what might a global “war on terrorism” bring forth? At what point do we try to end the cycle?

With these issues in mind the Vatican, hardly an institution known for its radical liberalism, has come down on the side of peace. Last week Pope John Paul II made a call, in no uncertain terms, for people “to pray for peace and to be committed to building a world without violence, founded on respect for the dignity of every human being.”

Regardless of these pleas for peace, many right-wing religious Americans have continued to call for war. Often, they do not use Biblical passages supporting war, quite simply because such passages are not particularly prevalent in the Bible. Instead they use passages of solace or comfort, such as that from Psalm 23 which President Bush recited the night of Sept. 11, and do so in conjunction with their own battle cries. It’s a bit like beer commercials filled with beautiful people. They of course can’t claim that drinking beer will make you look like these people any more than one can claim that Jesus’ teachings support war, but the hope is that somehow the viewer will associate drinking beer with beautiful people, religion with a war. When not quoted out of context or misused, the Bible calls for peacemaking and love. These words come from the war-making president’s alleged “favorite philosopher,” Jesus:

I tell you who hear me: Love your enemies, do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, pray for those who mistreat you. If someone strikes you on one cheek, turn to him the other also…Do to others as you would have them do to you. (Luke 6:27-31)

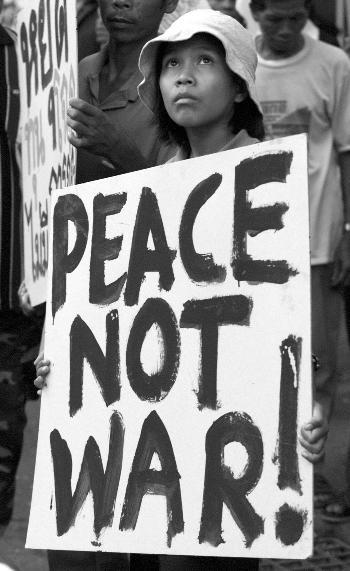

Peace activists may piss you off, Lord knows they bother me. But to spend our time belittling the antics of sanctimonious, wannabe hippies misses the valid arguments for peace: that the US must seek to shore up international support to help arrest and prosecute current terrorists. That in the attempt to bring these terrorists to justice we must avoid the foreign policy mistakes that helped give rise to violent extremists like bin Laden. And finally, that the country must try avoid the deaths of innocent civilians, who will be mourned by friends and family as bitterly as those who died on Sept. 11.

Joseph P. Flood ‘03 is a English Concentrator in Mather House.